About the Author:

Teana Graziani is a Master’s student of journalism at Ryerson University in Toronto who has written a feature about Polish people who were deported by the Soviets to Siberia, and relocated to refugee camps in the British colonies in Africa during World War II.

Teana Graziani is a Master’s student of journalism at Ryerson University in Toronto who has written a feature about Polish people who were deported by the Soviets to Siberia, and relocated to refugee camps in the British colonies in Africa during World War II.

The story focuses on the experiences of two Canadian Poles

Interview with Teana Graziani:

How the first modern refugee camps in Africa were in fact for white Europeans

Flames burst upward like solar flares, devouring the tall blades of elephant grass, and morphing into clouds of thick, black smoke that drift into the sky. Animals struck with confusion and fear scamper across the African grasslands to safety, and people nervously watch from their huts as the raging flames approach the Polish settlement in Masindi, Uganda.

Among those observing the horrific scene is a young Polish boy named Romuald Kubisz, taking in all of the chaos through his eight-year-old eyes, that have already seen so much.

The day following the great fire, Kubisz leaves school and heads out into the grasslands to collect some pepperfruit with his twin brother Krzysztof and their friend Czesiek. As the boys wander amid the incinerated brush, a wisp of smoke rising from a burnt log catches Kubisz’s eye. He sees an opportunity to roast their peppers if they use the smoking embers to start a fire. The boys begin piling brush onto the log and with help from the wind, a fire catches. The flames continue to grow at an uncontrollable speed. Not knowing what to do, the boys stand around the fire in total panic, until they hear a noise coming from behind them.

Running towards them, waving his arms and shouting hysterically, is Joseph, the native watchman and policeman of the settlement. The boys run off as fast as they can, leaving Joseph to tame the merciless blaze on his own. They have escaped punishment, but only temporarily. They arrive home hours later to find Joseph, standing in front of their hut along with Mrs. Kubisz, who has look of severe displeasure strewn across her face.

“He [Joseph] must have recognized me, as this was certainly not our first encounter – I was quite the rascal,” says Kubisz with a chuckle, while sipping a hot cup of tea in the living room of his Toronto home.

Kubisz’s childhood in Masindi is a story filled with countless antics and adventures. His memories from nearly 75 years ago as a Pole forcibly displaced by the Soviets have not faded, and still shock those whom he shares them with.

Kubisz, like many other Poles in the wake of the Second World War, had his fate chosen for him. Poland’s territory was heavily sought after by major military powers, however, its population was not valued in the same way – resulting in mass deportations that would ultimately be the first step in the dispersion of hundreds of thousands of Poles around the world.

It has been 75 years since the commencement of the second World War, and with no shortage of stories emerging from those six years of tragedy, there are still many that have been left untold. It is a widely unknown history, that is, the existence of Polish settlements in Africa. While much attention and emphasis has been rightfully placed on the Jewish Polish community and the tremendous discrimination and suffering that they faced, few know about what happened to other groups of Poles, particularly Christians from the eastern part of the country, and about how the first modern refugee camps in Africa were in fact for white Europeans.

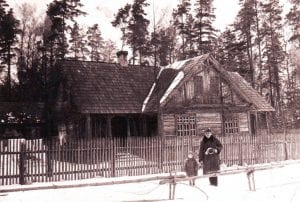

Kubisz was born in the hamlet of Zubowski Gaj, Eastern Poland; what is now part of present day Belarus, in 1937. It was there that he, his parents and his two siblings lived in a spacious wooden lodge with large colonial style windows on its front. The property was delicately lined with a wooden fence, and surrounded by a thick forest accompanied by a sea of flowers that would bloom in the warmer months.

During this time, Poland was recovering from over a century of being fought over by three major empires; the Prussian Empire, the Habsburg Empire, and the Russian Empire. After Poland regained its independence in 1918, it was stitched together from those parts that had previously been under strict, yet separate influence.

Eastern Poland was territory that in the past had been under the influence of the Russian Empire, and it was by far the poorest, most underdeveloped part of Poland. The region was far less urbanized in comparison to Central and Western Poland, and had nearly no established industry. Its inhabitants were predominantly peasants, who commonly worked as artisans, small landowners and outdoorsmen.

It was at this time that both of Poland’s powerful neighbours, Germany and Russia, were unhappy with the conclusions of the Treaty of Versailles; the peace treaty signed in 1919 that put an end World War I. It blamed Germany for starting the war, and as punishment, imposed harsh penalties on the country that included loss of territory, massive reparation payments and demilitarization. Germany saw the treaty as unfair, and wanted it overthrown.

“Poland was annoyingly in the way,” says Dr. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, Professor of History at the Center for Intermarium Studies at the Institute of World Politics. “Thus, the Poles felt an increasing enmity of the Soviet Union and Weimar Germany, later the Third Reich, throughout the interwar period. Both were hell-bent on destroying Poland.”

And so it began. Shortly after four o’clock in the morning on February 10, 1940, there was a brash pounding on the front door of the Kubisz family home. Before anyone could react, the door was thrust open by a large man dressed in plainclothes, accompanied by two burly Russian soldiers. The man curtly informed Kubisz’s family that they were being resettled based on the orders of comrade Stalin. They were instructed to gather the bare essentials, and were then sternly directed onto a horse drawn cart waiting outside that would take them to the railway station.

Kubisz’s long-time friend Helena Kucharska is from the region of Wołyń, Eastern Poland, present day Ukraine. Kucharska, her mother, and her six siblings had a similar experience of unexpected invasion and forced deportation by the Soviets in the early hours of the morning on that same day.

“I don’t remember it too well, I was very young,” says Kucharska, “but I know when they came to take us, there was no choice – we had to go.”

These, “wake up calls,” were done intentionally in the middle of the night by the Soviets to catch people off-guard and to avoid unnecessary attention. That night, around 140,000 civilians in Eastern Poland were forced from their homes in the same way, and over the course of that year, close to 400,000 civilians were deported from Eastern Poland up to the Russian white north.

The deportations were the result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed between Germany and the Soviet Union in Moscow in August of 1939. It was a non-aggression pact that secretly divided up Polish territory between the two powers. The pact declared that Adolf Hitler and his Germany would take the Western third of Poland, and Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union would take the Eastern two thirds of the country.

“In the eyes of Stalin, the Poles represented everything that he hated,” says Dr. Katherine Jolluck, Senior Lecturer of History at Stanford University. “In order for him to Sovietize the territory, he needed to decapitate the nation. He [Stalin] did this by forcibly removing all political, cultural, and economic leaders in Eastern Poland, along with their families. This included priests, school teachers, and anyone else who could maintain the Polish culture and stimulate resistance against Sovietization.”

As a result of their troubled past, Poles were fiercely nationalistic, and devout Catholics. This posed a threat to the imposing Soviets, as the Communist state was both anti-nationalist, and anti-religious.

Chodakiewicz says, “The Christian Poles were the main group targeted [by the Soviets], although they were certainly not the only ones who were affected.”

These Poles were the civilian deportees who were exiled into the Russian north – and Kubisz was one of them.

“The voyage was excruciating from what I have learned. You must remember, that I was very young at the time, about three years old,” says Kubisz.

Upon their arrival to the train station, Kubisz and his family were herded like livestock into cattle cars. There were 50 people per car. Each car had a wood burning stove and no windows. As soon as the car was full, its large wooden door was closed and bolted so that no one could escape. A hole in the middle of the floor functioned as a toilet. The combined stench of urine, excrement and vomit was absolutely foul, and was to be tolerated for the duration of the journey. Passengers were given just enough food to keep them alive. It was survival of the fittest.

“We were usually given cold barely soup and salted herring,” says Kubisz, “sometimes some stale bread. Hunger was our constant companion.”

Many of the passengers did not survive the nearly three week trip north, and their bodies were removed from the train only when it stopped to pick up supplies.

Kubisz says, “My family was sent to Arkhangel’sk [Russia], which is on the White Sea, around 1000 kilometres north of Moscow. Others were sent even further beyond the Ural [mountains], into Siberia.”

There were thousands of locations where the Soviets carelessly dumped groups of Polish deportees, and forced them to labour.

“There must have been at least 100,000 of such installations if not more,” says Chodakiewicz, “[that is including] sub-camps and even smaller installations.”

Jolluck explains, “Generally, the deportees were taken to some of the worst, most inhospitable parts of the Soviet Union. Often they had to build their own barracks or dugouts. The places weren’t prepared for them, and so oftentimes the Soviets would drop the civilians in a wooded area and say, “Alright, there’s a forest we need cut down, this is where you are going to live,” and they [the Poles] would just have to survive as they could.”

Barracks were small, and made out of wood. They typically had a single woodburning stove in the centre – their only source of heat, which was often insufficient at best, especially throughout the frigid Russian winters.

Like Kubisz, Kucharska’s family was settled in Arkhangel’sk. She recalls the abysmal living conditions, “I would be in the house with my brother and the ceiling would be leaking,” she says. “We would put pots underneath to catch the rain, as the roof was just no good.”

The Poles were settled in civilian deportee settlements and not forced labour camps, however, both men and women were required to work. Women worked at the settlement as homemakers and in the nearby factories producing items that were needed by the Soviet army. Men worked predominantly outdoors providing physical labour; clearing roads, chopping down trees and loading logs. All forms of work were hard and demanding, and had terribly long hours. Food was scarce and many deportees were undernourished, and became ill.

“At one point while in Russia, I became grievously ill, so much so that last rites were performed over my body, and prayers offered for my soul,” says Kubisz. “And yet, I defied the odds and pulled through.”

Luckily for many civilian deportees, the Russian nightmare lasted less than two years.

In June of 1941, Hitler and the Germans faulted on the non-aggression pact and invaded the Soviet Union, causing the German-Soviet war to commence. The Soviet Union all of a sudden found itself at war with a power that was incredibly strong – the Nazis. Initially, the war was not proving well for the Soviets, and they desperately needed every able-bodied soul they could get to help fight against Hitler.

On July 30 of that year, the head of Polish government in exile based in London, England, General Władysław Sikorski, negotiated a pact with Stalin that would allow the release of all detained Poles in order for them to form an army to fight alongside the Soviet Union against the Germans.

All Poles were free to leave the settlements by their own means. People flocked to trains that would take them to the southern parts of the Soviet Union, primarily to what is present day Kazakhstan. There they would find collection points where the men could join the Polish army led by General Władysław Anders – a Polish General who had been released from Soviet prison to do the job.

Of the nearly 400,000 Poles that were deported, only about 150,000 made it out of the Soviet settlements.

“Some of the settlements were in some of the most remote areas of northern Russia and Siberia, and during wartime, information didn’t travel all that well,” explains Jolluck. “Oftentimes the heads of settlements didn’t bother to inform the Poles of their rights. Also, a lot of Poles didn’t have the proper documents, or even the money needed to get on the trains, so they had no way of leaving.”

For those who had the means, leaving the settlement was an opportunity not to be passed up.

Kucharska remembers, “When Stalin said, “Ok, go,” people sold anything and everything they could to get a ticket onto the next train going south. It was a matter of life or death.”

Stalin had envisioned the new Polish army as becoming part of his Red Army, but Polish General Anders refused, and insisted that the Polish army be independent while fighting alongside the Soviets. Stalin negated this, refusing to allow a Polish armed force assemble on Soviet soil.

As the Soviet Union and Britain had now found themselves fighting a common enemy, General Anders took it upon himself to persuade the British government to take on the Polish forces, and the British in turn, persuaded Stalin to let them take the Polish soldiers and their families out of the southern parts of the Soviet Union.

The Poles were brought across the Caspian Sea to the nearest British patrol territory in Persia, present day Iran. It was there that the British began to organize the Poles. Many of the Polish soldiers went on to join the Royal Army. The families they left behind were classified as displaced persons by the British, and were sent to the British colonies; some in British India and modern day Pakistan, as well as parts of British East and Central Africa such as Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya, amongst others.

“When we went to Persia, I remember the great feeling of finally having heat and food,” says Kubisz, “I could eat as much as I wanted to! It was so, so warm, and we never felt hungry again.”

Kubisz, along with his mother and two siblings stayed in the city of Tehran for a couple of months, until they were directed by the British onto a ship that over the course of three weeks would take them to British East Africa, where they would ultimately settle in Masindi, Uganda in 1942.

Kucharska’s experience was similar; “I remember the incredibly hot sand in Persia before we left on the boat to Africa,” she says. “It was a much welcomed change from the Russian cold.”

“Which colony families were sent to was decided by the British administration who were in correspondence with the colonial governments,” says Dr. Jochen Lingelbach, Research Assistant at the chair of African History at Bayreuth University. “Colonial governments would just say, “We have space, send us any 3,000 people,” and the British administration in Iran would organize and send the people out, and that would be that.”

Lingelbach continues to explain, “Most of these refugee settlements would have remained open until the late 1940’s, early 1950’s [after the war was over], when nearly half of the displaced Polish population left for the United Kingdom. They were allowed to join their relatives who had served in the Polish army, because that was where the army was demobilized [in the UK]. Others with no direct relatives in the army were not allowed to go [to the UK],” he says. “Some people got Visas to countries that were resettling displaced persons, and others voluntarily went back to Poland.”

There were a total of 24 Polish settlements across six countries in British Central and East Africa, and more in other countries around the world including present day India, Pakistan, México, New Zealand and Australia.

Kucharska along with her mother and a few of her siblings were sent to Tengeru, Tanganyika, present day Tanzania, in 1942. It was the largest of the Polish settlements in Africa, housing up to 4,000 displaced Poles.

Masindi, Uganda where Kubisz’s family was sent, was also one of the larger Polish settlements in Africa, housing around 3,000 displaced Poles. The settlement in Masindi had quite literally been carved out of a thick, vast, tropical forest, and remained surrounded by it. Uganda’s consistently hot, tropical climate was what gave life to its Savannah plains, which were dominated by grasslands that bordered the settlement, dotted with Borassus palms, elephant grasses and Mvule trees.

The British had prepared the settlement to house the incoming Poles. It was a proper camp fully equipped with named streets, and huts that had been built by African workers as per British instruction.

There was a hut for each family. They were simple; small and round, made primarily of mud, and painted with plaster to make them white. The roofs were made of thatched banana leaves, turned golden by the beating hot sun. The floors were made of clay. Community kitchens were shared amongst neighbours. There was a church, an elementary school and a hospital.

“Tengeru was much the same, but we also had a gymnasium,” recalls Kucharska. “And we had a community farm. There were chickens and pigs, and vegetable gardens. And I would go shopping at the local market with my mother to buy fruit and other things. Our clothing was supplied by the [United] States – they were all donations because we all had such little money.”

The British gave the Poles what they needed to start building their own communities, and then left them on their own to take care of themselves, with the exception of one British camp commander per settlement. It was the job of the camp commander to keep an eye on the settlement, and to report back to the British administration.

“The British would have supplied the settlements with some livestock and other necessary infrastructure, such as schools, but the Poles would have built on what they were given, so things like the local church would have been built by them,” says Dr. Lynne Taylor, Associate Professor of History at the University of Waterloo. “The British mentality was to make the Poles as self-sufficient as possible, but to always keep them under their control, since they were the ones footing the bills.”

Life in Africa certainly looked nothing like what many Poles were used to, especially when it came to dealing with Malaria; an infectious disease that is common in many African countries, and spread by mosquitoes.

“Everybody went through Malaria including myself – I had it twice,” says Kucharska. “To cure it, there was a drink that you’d have to take for seven days, and then for the next seven days you had to take tiny yellow pills that you couldn’t even swallow. They were so bitter you could scream!”

The weather in Africa was also very different from that of Poland. Existing along the equator, Uganda was much more humid and far hotter than any weather Kubisz would have experienced back home, too hot, in fact, to walk in his bare feet.

“It [the ground] would only cool down when it rained,” he says. “And the thunderstorms, by George, they were terrible! They would come frequently during the [rainy] season, and almost without warning. Instantly. Torrential downpour. The storms were so violent and always terrifying. Even to this day I feel uneasy about thunderstorms—they still make me nervous. After all, my mother was killed by a bolt of lightning during one of those storms.”

The two friends laugh and reminisce the good times of their childhoods in Africa between sips of tea and bites of traditional Polish confectionaries. Vivid memories of the noteworthy African wildlife are recalled excitedly by both of them, one after the next.

“Oh, the monkeys! There were lots of monkeys,” says Kubisz. “I remember on one occasion we were having a campfire at night, and they were sitting in the trees and throwing sticks at us.”

Kucharska reminisces, “Near Tengeru there was a nice river where we used to go swimming and see the monkeys that would sit around on the branches. They would make noises at us while we swam,” she says.

Kubisz recalls another animal story; “In Masindi, there was a huge gorilla that was kept in a cage—it was a pet. One day it escaped and, oh, that was a consternation in the village!”

He carries on to top his last story with another; “I remember when they killed a python that was 18 feet long. They said I was lucky that it didn’t eat me, because it had just swallowed three chickens whole, and I was just a little boy. Then they killed it. The skin was sent to Kampala where they made purses and shoes out of it, and then we had a huge bonfire at the settlement and ate the meat. I hated it.”

To everyone’s surprise, Kubisz manages to top his previous story with his next one; “Oh, and the termites! Yes, we would just eat them like that, right off the wood – delicious! And now you see people eating insects here, today. It is becoming quite fashionable. You see I paved the way for them!”

As the stories start to come to an end, Kubisz grins. “It may not have been a traditional Polish childhood, but then, nothing was traditional about thousands of Polish people living in Africa,” he chuckles.

And he could not be more right. During times of war, circumstances changed for everyone. Many Polish customaries were not possible for Poles to practice until they left the African settlements after the war, and settled into their new homogenous communities in Britain, and other parts of the world. As a result, during their time living on the settlements, Poles had to adapt, and ate whatever was available to them – often foods that were not part of the traditional Polish cuisine. But that was to be expected.

After all, Africa is known for many things, but pierogies are not one of them.

.jpg)