Muthaiga Club w Nairobi to najstarszy, najdroższy, najbardziej ekskluzywny, najbardziej prestiżowy prywatny klub w Kenii – ba, w całej Afryce Wschodniej i Centralnej.

W dniu święta Dnia Niepodległości Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, wraz moimi rodzicami Dr. Kea Barua i Dr. Aurelią Kawczyńską-Barua, moim bratem Jakubem Barua, oraz moją córką Stefanią Barua, wjeżdżamy na teren tej owianej legendą posesji. Bujny, wypielęgnowany ogród otacza niskie budynki mieniące się różowo w złotym świetle zachodzącego, równikowego światła.

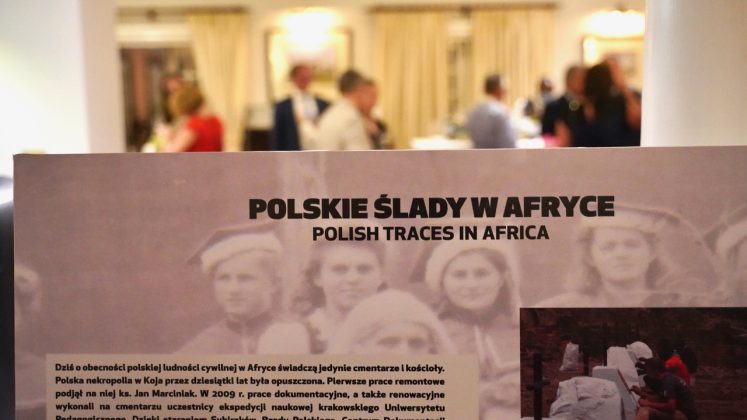

Wchodząc wewnątrz przez główne wejście, dochodzimy do niedużej sali znanej kinomanom z filmu fabularnego „Pożegnanie z Afryką”, z Robertem Redfordem i Merryl Streep, w której odbywał się bal sylwestrowy. Dookoła sali zauważamy wystawę zdjęć, opisów, plakatów poświęconym Polakom we Wschodniej Afryce między 1942 a 1952 rokiem. Flaga Polski, Kenii, oraz Unii Europejskiej.

Dostojni goście rozmawiają między sobą. Kelnerki dyskretnie obnoszą zakąski i napoje. Dochodzę i przedstawiam się Panu Ambasadorowi J. E. Jackowi Bazańskiemu i jego małżonce pani Annie Bazańskiej, dziękując im za ich tak hojne zaproszenie mnie oraz mojej córki, która jest tutaj z Lublina. Mam zaszczyt i radość też przywitać się z Sapieżankami Kasiunią i Maryjką, których nie widziałem wiele lat. Wśród przybyłych są ambasadorowie garstki krajów, i pracownicy przedstawicielstw różnych państw – Pan Ambasador Tunezji w Kenii J. E. Hatem Landoulsi studiował w Polsce pod koniec lat 80-tych i jest tu ze swoją małżonką, Polką. Zamieniamy kilka słów o naszym wspólnym znajomym Chaouki Mejeri, tunezyjskim reżyserze filmowym, z którym mój brat i ja studiowaliśmy w łódzkiej filmówce, a zmarłym kilka lat temu.

Są też, oczywiście, pracownicy polskiej placówki dyplomatycznej w Nairobi; są Polacy pracujący w wielkim kompleksie ONZ-towskim UNEP/Habitat – wśród nich znajomy nam Tomasz Sudra (urbanista, architekt, uciekinier z lat 70-tych, absolwent amerykańskiego MIT, od 1984 osiadły w Nairobi wraz z małżonką, Szwajcarką, p. Ines Kenka-Sudra); inni Polacy mieszkający w Nairobi – p. Rhodia Mann (pisarka, historyczka plemion kenijskich, córka Eryki Mann autorki kolonialnego planu miasta Nairobi z 1948r. i innych miast Kenii), niektórzy wraz z rodzinami; Kenijczycy, w tym kilku, którzy studiowali w Polsce – Benedict Odongo, który na przełomie lat 80-90-tych studiował na Politechnice łódzkiej, Ghanejka Ama Musee, która wraz z mężem Kenijczykiem Milo Musee studiowała na uniwersytecie w Poznaniu; polskie siostry zakonne ze Zgromadzenia Najświętszej Rodziny z Nazaretu pełniące posługę na misjach w kilku częściach Kenii i Zambii; oraz przyjezdni Polacy z kilku rozległych zakątków świata – Pani tancerka baletowa z Los Angeles, Pani sędzina która w 2008r zasiadała w trybunale Khmer Rouge… Zamieniam też kilka zdań z dwoma młodymi Kenijczykami – reżyserem i producentką filmową – przybyłymi, bo „zamierzają nakręcić film dokumentalny na temat Polaków w Kenii”; przekazuje im informacje o mojego brata filmie o p. Janinie Roche „Mój tatuś był ułanem”.

W sumie jest obecnych ponad sto osób.

Rozmowy ustają. Pan Ambasador Bazański przemawia do gości, zapraszając do podium Panią Maryjkę, Sapieżankę, jak ją zwą tutaj jej liczni przyjaciele. Zamieniamy się w słuch. Księżniczka Sapieha przemawia w języku angielskim. W mgnieniu oka, przenosi słuchaczy w świat represji, zbrodni, zdrady, komuny, uchodźctwa, lecz też w świat bohaterstwa, heroizmu, poświęcenia, odwagi, wytrwałości, patriotyzmu, oddania, nadziei.

Zaczyna od historii swojego dziadka, księcia Eustachego Kajetana Sapiehy, szlachcica z Kresów, przedwojennego polityka, i od 1919r. Ambasadora II RP w Londynie. W wojnie polsko-bolszewickiej 1920r. służył w kawalerii, po czym był mianowany na Ministra Spraw Zagranicznych, a później był deputowanym na Sejm 1928-29r.

Gdy Sowieci wkroczyli do Polski w 1939r, został aresztowany i uwięziony na Łubiance…

“Molotow had signed a secret agreement on 28th of August 193, just before the beginning of the war to take over and start conquering the world, so to say, and Poland was the first to go.

The whole of eastern Poland was taken over within a few days and was proclaimed an independent country.

My grandfather got a call from the Red Cross and worked closely with the colonial government here in Kenya to establish camps for tens of thousands of civilian people. Those are on the posters that you see here, which (Emma) will explain to you later. Prince Sapieha had been very active in setting up refugees’ camps during the First World War, in 1916, and perhaps – we are not sure, but it could be – because of this that he was chosen for this mammoth task.

June 1941 saw the attack of the Soviet Union by its ally, Germany, in the Operation Barbarossa.

Following Operation Barbarossa, Stalin declared an amnesty of Polish prisoners and, literally, the Gulag gates were opened. This resulted in uncountable amounts of Poles stranded in the USSR. British historian Norman Davies, who is also quoted in one of the exhibits here, writes in his book “Trail of Hope”: “One can only hint at the ocean of human misery endured by the flood of ex-prisoners and ex-deportees (mostly heading towards Iran in the south). Many of them fell by the wayside, stricken by exhaustion, disease, and utter despair”.

It is difficult, actually impossible, to give exact figures of how many survived the terrible conditions. Thousands died during the time the 1.7 million were thrown into the over 200 different Gulags situated throughout Russia. A little later, even more were trucked into Kazakhstan. The now starving people went into Gulags where the conditions were terrible. Now suddenly, in 1941, they found themselves literally just flung out, not knowing exactly where they were on the map, and told to just go.

Stalin’s amnesty lasted until the beginning of 1943 when, again, from one day to another borders were closed.

The German army discovered 22,000 Polish officers shot. This was near Smoleńsk, in Katyń. Vehemently, Stalin denied that the Soviets were the culprits, and decidedly cut diplomatic relations with the Polish Government in Exile in London, accusing them of being Nazi sympathizers. Soviet borders were closed. Forty years down the line, Gorbachev owned up to the Soviet crime. But it was only in 2010, seventeen years later, that the Russian Duma officially accepted Soviet responsibility for the Katyń massacre.

Unfortunately, in Britain the Soviet denial and propaganda was believed, and it repeated Soviet slurs against the Poles. I again quote Norman Davies: “The British, like the Americans, viewed the Second World War in somewhat naïve, simplistic, and self-righteous terms. They convinced themselves they were fighting a good war, and that Adolf Hitler was the embodiment of incomparable evil. In essence, Germany was the enemy and Russia a traditional friend.”

By now, Stalin had completely bamboozled Roosevelt. And even Churchill fell under Stalin’s “charm”.

After the amnesty, and as the emaciated Polish Army was being formed at the southern borders of the USSR, Iran was offered as a place of respite. In Iran, until 1942, the Polish Army under General Anders passed under British command. The Poles and the British authorities in Iran were burdened to organize facilities for the enormous influx of malnourished and disease-ridden Polish refugees. General Anders wrote that his most urgent task was to organize proper medical care and accommodation for the civilians.

The condition of the newly arrived was appalling, often beyond rehabilitation. Temporary, well-organized transit camps were established while able-bodied (or feeble-bodied?) men and women became part of Anders’ army.

At the first instance, the Poles in conjunction with the British Army turned for help to the Government of Iran, and then to the Colonial Office in Britain, and to the exiled Polish Government in London seeking where to send civilians. Destinations such as East Africa, India, Canada and New Zealand were identified in the vast British Empire, with Mexico and the US agreeing eventually to accommodate just a few hundred deportees.

More than half the civilian Polish exiles were sent to East Africa, the Rhodesias and South Africa. Some 20 smaller camps accommodating 300-400 people were strewn all over East Africa, with the largest three accommodating between four and six thousand individuals each were built in Tengeru near Arusha, in Koja and in Masindi.

The colonial government did not want the camps too close to any city as suddenly the influx of new Europeans to East Africa had absolutely, completely doubled. Undeniably, despite great difficulties, British colonial authorities went out of their way to help. Most deportees were incomplete families as most of the women were widows with children. Some had their husbands in the military. There were thousands of orphans. All the camps were islands of Polishness, with churches and schools set up by the Poles. These were quickly organizing themselves despite very primitive conditions in Africa. But conditions in the camps were idyllic in comparison to the nightmares of Siberia.

1945, after Yalta, the camps were dismantled bit by bit. The last left in the early 1950s. And here amongst us are a few of the progeny of some of these people who ended up here. One of them is Bożena Insol who was born in one of the camps; there is someone who returned from England who is from here and has been here 20 years – Anna Stabrawa; there is Rhodia Mann, whose parents were not in Russia but came to Zambia as part of the consignment; and there is my sister Teresa and I who are the progeny of some of the people who came through those camps.

Eustachy Sapieha, in spite of his age and severe disability, left Iran – as I had said – for East Africa in 1942. He never spoke of Lubyanka or the Gulag. Like all these Poles after Yalta, he found himself penniless, having both lost his home and his country. Lie hundreds of thousands, no! millions of Poles, he found himself stateless and unwanted. Although he was given special immunity to be able to stay on in Kenya, 7 years down the line in 1949 his wife – my grandmother – came to join him, coming down the Nile, which was organized by the Red Cross.

My parents soon joined them. My father had spent nearly 6 years as a German prisoner of war. As my mother was a hero, a soldier of the Polish Home Army (AK), my sisters and I were born here.

By June 1945, in line with the Yalta agreement, the USA and UK withdrew their recognition of the Polish Government in Exile and recognized the newly set up Provisional Government of National Unity in Warsaw, a communist government set up by Stalin’s lemmings. Approximately 100,000 Polish troops were still serving under British command. And after 6 years, the same Poles who had diligently served the British – and even worse – were suddenly outlawed.

In spite of being treated as vanquished enemies and having been robbed of their home and their freedom, the tenacity of these Poles can only be admired as they started new lives in new countries.

“In 1945, Poland was a martyred nation, which was abandoned and condemned to more and more moral and physical misery”, wrote the British historian of Polish origin Adam Zamoyski in his book “The Polish Way”.

One year later, 1946, a grand victory parade took place in London. Who was missing? The Polish comrades of arms from the Battle of Britain, the Battle of the Atlantic, Battle of Tobruk, from Monte Cassino, from the thousands upon thousands… [Here, Princess Sapieha breaks down sobbing]… of air battles… [She composes herself].

But now the story of these displaced people is no longer just a footnote… [Her last words trail off inaudibly].

Po słowach Księżniczki, Polacy i goście są zaproszeni do skosztowania pysznego bigosu, przyrządzonego przez kuchnię Muthaiga Club, według receptury i pod nadzorem Pani Bazańskiej.

PS. 12 grudnia Kenia obchodziła swój Dzień Niepodległości

Stanisław Barua